This May, I tore two tendons in my rotator cuff, and had to get surgery, followed by a 6+ month recovery process. My surgeon prepared me for some of what was to come, but much of it caught me by surprise. For example, I expected some pain, but I didn’t know that the pain medication wouldn’t work on me at all; I expected to have trouble sleeping, but I didn’t know I’d have to sleep in a recliner for 2.5 months; I expected it to affect my productivity, but I didn’t know I’d need to spend an hour+ each day on rehab exercises and have to re-learn how to tie my shoes, get dressed, and brush my teeth. This blog post is my attempt to share my experience so that anyone going through shoulder surgery in the future can have a better idea of what to expect.

Here’s an outline of this blog post:

Let’s start by talking about how I got my injury in the first place.

Injury

Hanging off a cliff one-handed. Fighting off a grizzly bear. A brutal knife fight. These are all the ways I didn’t injure my shoulder. But they are a lot more interesting than the real story: I sat down on a bench, grabbed a 65 lb dumbbell from the floor, yanked it up on to my knee, and felt a tearing sensation in my shoulder.

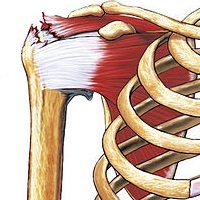

I’ve injured myself plenty of times at the gym, and rarely go to the doctor (there’s only so many times I can hear “you just need RICE: rest, ice, compression…”), but this time, I felt something was seriously wrong, and got an MRI. The results were clear: I had major tears in the tendons that attach the supraspinatus and infraspinatus to the humerus (the arm bone). Here’s a rough sketch of the injury:

I met with a surgeon who specializes in rotator cuff repairs, and he told me the following:

- I must have had a previous injury: Picking up a 65 lbs dumbbell was very unlikely to cause such a major tear; I must have already had a partial tear from some previous injury. I vaguely recall injuring my shoulder doing heavy bench press some 8-10 years ago, though I had no idea at the time it was a tendon injury, as it seemed to heal after a few months. I guess in reality, these sorts of small tendon tears never actually heal; you can build strength around the injury, but there’s always a risk the small tear turns into a large tear later on.

- Surgery was my only option: Given the size of the tear, if I didn’t get surgery, I’d never have full use of my right shoulder again.

- I needed surgery immediately: With these sorts of tendon injuries, you have to get surgery within 6 weeks (at most), as after that point, the detached tendon is often too deteriorated, and can no longer be used. If that happens, the only option is to get a tendon from a cadaver, and the results with that type of surgery are not nearly as good.

So, a couple of weeks later, I got the surgery.

Surgery

The surgery itself was not too bad. I was in and out the same day. It’s the recovery that’s tough; but more on that later.

The process was pretty straightforward. First, I changed into a hospital gown. Next, as I’m a somewhat hairy guy, one of the nurses had the unlucky job of shaving my shoulder, and parts of my chest (I guess chest hair interferes with electrodes?), so I looked a bit like Steve Carell after the chest waxing scene in The 40-Year-Old Virgin.

Next, they hooked me up to the machine that checks vital signs. My resting heart rate is in the high 30s, and sometimes dips into the low 30s, so that machine kept thinking I was dead, and setting off alerts. Always a good sign before surgery! After that, the surgeons came in, had a brief chat with me, double-checked who I was, what procedure I was getting, and on which shoulder, and then wrote on that shoulder with a marker. A bit weird, but I suppose that’s better than getting the wrong procedure on the wrong body part. Then the anesthesiologists came in, put me on general anaesthesia, and then… I remember nothing.

Next thing I know, I’m waking up in a different room, with some other nurse I haven’t seen before, wondering when the surgery will start. The nurse smiles at me, and I follow her eyes down to my shoulder, where I discover there is a sling, and a huge bandage over the shoulder. Oh.

The operation itself took around an hour. The pre-op stuff was also about an hour, and recovering from anaesthesia is another 1-2 hours, so roughly 3-4 hours total from start to finish. After the operation, I was a bit groggy, and I felt discomfort from having my arm in a sling, but no real pain (that would come later). In fact, I couldn’t feel my arm at all. Everything from the shoulder down, as well as part of the chest, was completely numb. Holding my number right hand with my left hand felt like I was holding someone else’s hand. Super creepy.

My upper arm was also incredibly swollen. It looked roughly twice it’s normal size, and felt like it was full of fluid. This is because I had an arthroscopic surgery, where they cut 5 small incisions (rather than one large incision) in the shoulder, and they insert various instruments, including cameras, into those incisions to do the operation. As part of this process, they inject fluid, as it spreads things out more, which helps them see better. Your body eventually absorbs this fluid, but for a week or two, you’ll have a massive, squishy upper arm. I don’t have a photo from the day of the surgery, but here’s me roughly 3 days later, where you can see the sling, and some of the swelling (although it has already gone down a lot):

I went home after the surgery and spent the day relaxing. The next morning, I had a post-op appointment. The surgeon removed the huge bandage, leaving just small bandages called Steri-Strips (which come off by themselves several weeks later), over the 5 incisions. This looked much less scary. The incisions are pretty small, and after 6 months, they look like small pink lines that are hardly noticeable. Hooray for arthroscopic surgery!

The surgeon told me that he does around 300 rotator cuff repair operations per year, most of which are boring—but mine was a real challenge! He then showed me pictures he took during the surgery using the arthroscopic camera while enthusiastically narrating each step of the operation: cut holes here, drill anchors into the bone there, suture the tendons onto the anchors, shave the bone down to give the tendon more room, and so on. Seeing someone passionately talking about their life’s work is awesome; realizing that work is the inside of your body can be a bit surreal. I’m grateful there are people in the world willing to learn how to do operations like this, and that we have the technology for them; had I torn my rotator cuff this way 100 years ago, I’d probably have a bum shoulder the rest of my life.

The surgeon left me with this message: “We did a terrific job fixing your rotator cuff. Now don’t fuck it up.” OK, I’m paraphrasing slightly, but that was the gist of it. The point was I needed to do PT and be very careful with recovery, which I’ll discuss a bit later. But first, I’d have to get through a lot of pain.

Pain

Right after the surgery, I was surprised by how there was virtually no pain. “This isn’t so bad,” I thought. Oh, how wrong I was. But I wouldn’t know that for another 24 hours.

It turns out I wasn’t feeling pain due to something called a nerve block. Before my surgery, I had only heard this term used in science fiction. I remember a scene in Neal Asher’s Gridlinked where a soldier gets his broken arm repaired by a surgical robot: “A sharp pain in his shoulder, and Stanton looked around at the disc now pressed there. His arm went completely dead: nerve-blocker.”

It seemed so futuristic and magical, but it turns out that nerve blocks exist! You get a shot between your neck and shoulder, and you lose all feeling in your arm… For 24 hours. And then the pain begins. And gets worse. And worse.

By the end of the second day, I was literally writhing on the floor in pain. It turns out that having someone dig around in your shoulder, drill your bones, and do a little cross stitching on your tendons is rather painful. I don’t mean to scare anyone. Every shoulder, every surgery, and every person is different, and not everyone will feel as much pain. That said, I’ve heard that shoulder surgery, for some reason, is particularly painful—more so than knee or hip surgery, for example.

Of course, my surgeon prescribed medication to deal with the pain: namely, Percocet, which is a combination of Oxycodone (an opioid) and acetaminophen (Tylenol). I took it once I felt the pain starting to come on. That’s when I learned a fun fact about my family: Percocet (specifically, the Oxycodone part) doesn’t really work on us. Apparently neither my sister, nor my dad are affected much by Oxycodone. And as I learned the hard way, neither am I. What an awesome superpower. Even a double dose of Percocet did next to nothing for the pain. In fact, I suspect what little relief I got was mostly from the acetaminophen portion, so I took more Tylenol, which helped a little bit, but only up to a point (too much Tylenol can cause liver damage—look it up). I also wasn’t allowed to take NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or aspirin, as they interfere with healing after this type of surgery.

There was one thing that made a big difference: ice. Huge, vast, gigantic quantities of ice, all day, and all night. This was the only thing that significantly reduced the pain. But there was a catch: having to change ice packs every 20 minutes, both to prevent frostbite, and because the ice melts, was a huge pain (especially at night). By pure luck, about a week before the surgery, a friend of mine had told me about a solution, and after struggling with significant pain for a few days, I finally followed my friend’s advice, and now I pass it on to you.

There are cold therapy machines which consist of a cooler you fill with ice (frozen water bottles work great) and water, and the machine pumps the cold water through a tube into a therapy pad you put around the injured area (e.g., the shoulder), with a programmable timer that cycles the machine automatically on and off every 20 minutes. That means you can leave the machine on all day and all night, with no risk of frostbite, and no need to run to the freezer every 20 minutes. There are several such machines on the market; I got the Polar Active Ice.

This thing was a lifesaver. I used it every single day for more than two months. It’s not cheap, and you do slightly resemble Mr. Freeze, but it’s worth it.

I’d recommend anyone getting shoulder surgery to get one of these devices. The first few weeks, I’d have it on all day long, as it let me keep the pain at low enough levels, so I could concentrate on work. After that, I no longer needed it during the day, but I still used it at night for many more weeks to help me sleep.

Sleep

The surgery caused a lot of pain, but far worse was the impact on sleep, for several reasons:

-

I had to sleep on my back. I’m a side sleeper, and hate sleeping on my back, but for a long time after the surgery, nothing else worked. I obviously couldn’t sleep on the side that was operated on, but it turned out I couldn’t sleep on the other side either, as the arm that was operated on would always slip into a painful position, no matter how I arranged the pillows.

-

I had to sleep in a recliner. Even when lying on my back, gravity pulled my arm into a position that was too painful after such an operation. I tried propping up my arm on various pillows, but I’d always wake up after a few minutes in pain. The only way I could sleep was to use a recliner to get my back more upright, so the arm wouldn’t fall back as far. Sleeping in a recliner is a common result of many types of surgeries, so if you’re having an operation, I strongly recommend buying or borrowing a recliner. I ended up sleeping in my recliner for 2.5 months. I tried many times to switch back to a normal bed before that, but it hurt too much.

I also had to learn how to sleep in a recliner without hurting my neck, lower back, or elbows. This video was a lifesaver. The short version: (a) use an airplane pillow under your neck, (b) put a rolled up towel under your lower back, (c) put pillows under each elbow, and (d) put pillows under your ankles. It’s a huge pain. The only good thing was my sweet cat, who kept me company every night while I was in the recliner.

-

I had to sleep in a sling. I had to keep my sling on for 6 weeks after the surgery, including during sleep. This was especially uncomfortable for the first two weeks, when I was required to use the stomach pillow with the sling, as that put pressure on my stomach and lungs (which is particularly uncomfortable in a horizontal position, and yet another reason I needed a recliner). I was tempted to take off the sling at night, but a few weeks in, I had one of those falling dreams, where, just as you’re drifting off to sleep, you suddenly feel like your falling, and woke up violently flaying my arms outwards—including my injured arm. It hurt like hell, but fortunately, the sling restrained my arm enough to prevent serious damage. Lesson learned: keep the sling on at night.

-

I felt a lot of pain at night. Despite all the above, I still found myself often waking up in pain and having to ice my shoulder, which was hugely disruptive to sleep. The solution: a cold therapy machine, as I mentioned in the previous section, which I left on all night (on a schedule). It’s not comfortable having a big therapy pad and hose on you all night, but the pain reduction is worth it.

Because of all the above, in the 3 days after the surgery, I slept a grand total of about 3 hours. I did not yet have the recliner or the cold therapy machine those first few days, so I tried sleeping in a bed, on a couch, in a chair, on the floor, on a yoga mat, and with every pillow construction I could think of, and nothing worked. The best I could do was doze off for 5-10 minutes, after which I’d wake up in tremendous pain, and have to go ice my shoulder for 20 minutes. Then I’d try again, and again, and again. It was miserable.

It was only after I got the recliner and the cold therapy machine that I was finally able to sleep for more than a few minutes at a time. After several weeks of getting used to it, I was eventually able to get good, but never great sleep. To paraphrase Steve Pucci, you eventually get to a point with sleeping in a recliner where you almost don’t hate it. Even if I slept 9 hours, I’d still wake up tired, and a bit sore (especially my shoulders and legs). There’s a reason virtually every human, everywhere in the world, through all of time, has slept in a horizontal position. You can never fully relax in a reclined position—some muscles are always working. Think about that: I wasn’t able to fully relax for 2.5 months.

After 2.5 months, when I was finally able to sleep back in my bed—on my side—I was ecstatic. I would go to bed with a giant grin on my face every single night—and I still do. I can’t express how much I appreciate being able to fully relax and sleep well.

As soon as I started sleeping in bed, I’d sleep 1 hour less per night, but wake up feeling much more refreshed, with nothing hurting. And this isn’t just a subjective feeling: I track all my sleep on my Apple Watch, and the difference was measurable. I could see in the AutoSleep app that as soon as I returned to my bed, I was getting more sleep, more quality sleep, and more deep sleep.

One other thing that helped with sleep was gradually being able to do more exercise.

Exercise

Exercise is a big part of my life. Before the surgery, I did a workout just about every single day. Working out after the surgery was… challenging. For the first 6 weeks, I was in a sling, there was a lot of pain, and the shoulder was in a very fragile state. During this time, most exercises were off limits: no running, biking (outside), swimming, or playing most sports; resistance training was very limited; even walking was painful the first week. This was tough on both my physical and mental health.

Despite all this, I still got back to exercising after about a week, and gradually ramped things up over time. I even bought a second sling so if I got one sweaty, I could switch to the other one (instead of walking around in a wet sling the rest of the day). Here’s what I did for exercise:

- Cardio. About a week after the surgery, I was able to walk and ride a stationary bike without pain, so these became my primary form of cardio. After another week or two, I added hill walking on good weather days and the stair climber when the weather was crappy. Once the sling came off in week 6, and the shoulder was a bit stronger, my cardio options opened up a little bit. I was able to go into the pool, starting with just floating (as a way to relax), and over the next several months, gradually working up to swimming with a kickboard (so just the legs were working), then doggy-paddle (which doesn’t use the shoulder too much), then breast stroke, and eventually, free style. Roughly 4 months after the surgery, I started running again. I held off on biking (outside) until month 6, as even a minor fall from a bike can be catastrophic until the tendon is fully healed.

-

Resistance training. Before surgery, I’d do resistance training using a combination of barbell exercises (squat, deadlift, press) and bodyweight exercises (push-ups, pull-ups, rows). After the surgery, I couldn’t do any of these exercises, as they either put significant weight on both arms (e.g., barbell press and deadlift) or on the shoulder girdle (e.g., barbell squat), whereas my healing shoulder was severely limited in its range of motion (especially while in a sling the first 6 weeks) and the weight it could hold (0 lbs for the first 2 months, but even 4.5 months after surgery, my surgeon was adamant that I not use more than ~15 lbs).

My solution was to switch to machines: e.g., leg press and hamstring curls for the lower body and one-arm press and one-arm rows (with my good arm) for the upper body. Using machines is not my favorite way to train, but it was better than nothing. I started very gently (light weight, high reps) to ensure I didn’t strain my shoulder, and gradually worked my way up. Note that I trained my good arm during this time, as there is some research that shows this can reduce muscle loss in the injured arm. As for the injured arm, I’d train that too, but mainly as part of rehab, which I’ll discuss next.

Rehab

Although I was in a sling for 6 weeks, which kept my arm mostly immobilized, my surgeon had me start doing physical therapy (PT) just 2 weeks after the operation. If you keep the shoulder immobilized for too long, you can end up with a frozen shoulder, where you can’t move it at all, and recovering from that is very difficult.

I was still dealing with a lot of pain, and my shoulder felt very fragile, so I was nervous in those first PT sessions. Fortunately, the physical therapists I worked with were great: a huge thank you to the team at Spaulding Outpatient Center, who worked with me the first two weeks while I was in the US, and Shane Kelly of Dalkey Physical Therapy, who worked with me for the next 6+ months. They gently, gradually got my shoulder moving again. There was a lot of pain, but it was the kind of pain where, after, I felt much better for having done it.

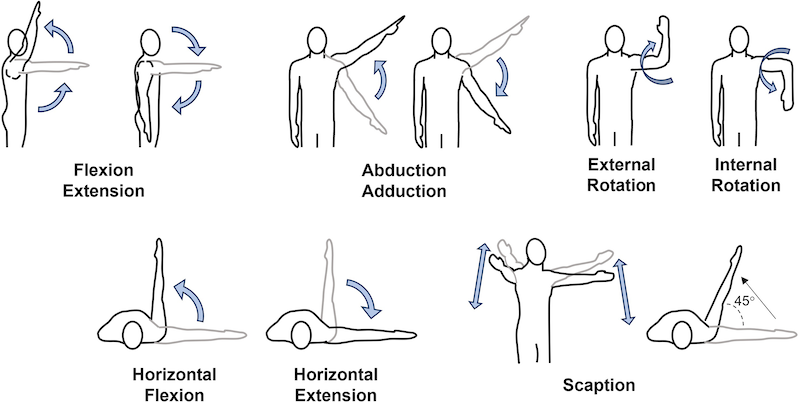

During my first PT session, I learned startling fact #1: I had very limited range of motion (ROM). Consider the following diagram, which shows the various types of movements you can do with the shoulder:

My flexion extension was less than 90 degrees, so even with a therapist moving my arm, I couldn’t get it straight out in front of me (let alone anywhere over my head); my internal and external rotation were even worse, at roughly 0 degrees (as in, I couldn’t turn my shoulder at all). Yikes. It was hard to believe that I could ever recover. That’s when I learned starting fact #2: while some of the loss of ROM was due to the surgery, much of it was due to my shoulder being immobile in a sling. Just a few weeks of immobilization is all it takes for tissues to become stiff and muscles to atrophy. It’s an unbelievable example of “use it or lose it.”

In addition to going to PT sessions several times per week, I also had to do exercises at home several times per day. These exercises were painful. That leads to startling fact #3: to heal an injury like this, some amount of pain is expected—even required. You’re aiming for a goldilocks zone, where it’s not too much pain, or you risk reinjury, but it’s also not too little pain, or you won’t force the tissues to adapt enough. So every day, I had to force myself to go through some amount of pain.

What kept me going through all of this was being able to see the progress. It was slow, sometimes excruciatingly slow, but there was progress. Just about every single day, I’d be able to do a movement for 1 more rep, or with a little less pain, or with 1 more millimeter of ROM. My mantra became:

1 millimeter of improvement per day.

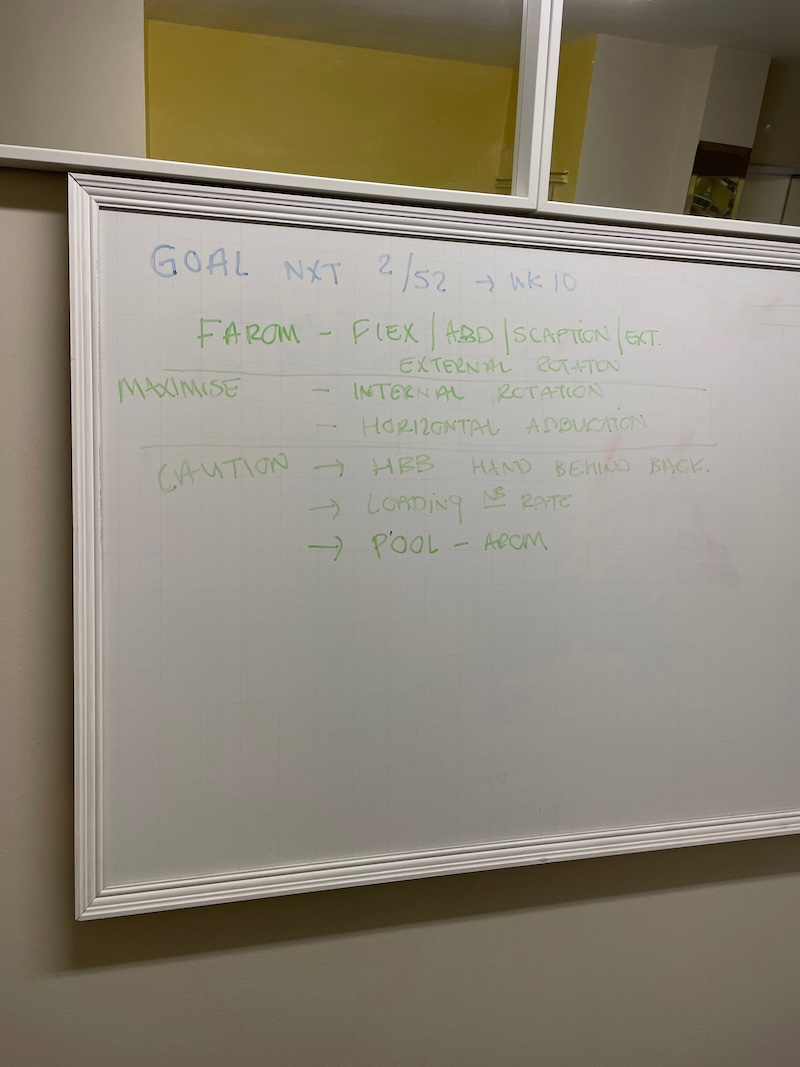

Over time, my range of motion and strength started to return; even my 0 degrees of internal and external rotation eventually returned to normal. But it took a long time. Here’s startling fact #4: it takes roughly 6 months for a tendon to heal fully, and you can’t rush that too much. At each stage, there was a limit to what motions I could do (e.g., no overhead movements until about 4.5 months) and how much load I could use (< 10 lbs until 4.5 months in, then < 15 lbs until 6 months). Once I reached 6 months, I was finally allowed to “return to activity.”

To get there, I had to do a lot of rehab exercises at home—as much as 1.5 hours per day! This is the reality with an injury like this: it takes a lot of your time.

Time

My surgeon told me up front that the recovery from this sort of surgery takes around 6 months. What I didn’t realize was just how much of my time during that 6 months would be spent on recovery. My productivity dropped significantly, due to the following:

-

Sleep. As I mentioned before, sleep took longer, and was not as restful (especially while I was in a recliner), so I was more tired, and less sharp.

-

Pain. Dealing with pain (e.g., changing ice packs) took time, and was a big drain on energy and motivation.

-

Rehab. The rehab exercises took a lot of time. They started out fast, but over time, they added up to an hour per day or more (spread across 3 sessions).

-

Relearning common activities. Common activities took longer, especially while one arm was in a sling or that arm’s strength and range of motion were limited. Here are just a few examples of activities I had to relearn:

- Tying my shoes one-handed. This video was a big help.

- Typing one-handed. I wrote much of my latest book one-handed. Dictation on iOS and macOS helped, at least for normal text (not so much for code).

- Putting on a shirt. This video was a big help.

- Brushing my teeth. Since I injured the shoulder on my dominant (right) side, I had to learn to do many things with my non-dominant (left) hand, including brushing my teeth.

- Showering. I had to get a loofa on a stick to be able to reach parts of my body.

- Flying. Going through security, carrying luggage, and putting bags into the overhead compartment are all slower and more complicated one-handed.

For the first month or two of the surgery, I’d estimate that I was operating at 50% of my normal capacity; maybe less. It was frustrating, especially as I’m a bit of a productivity nut. But gradually, slowly, it got better. I had to learn to be patient. I also learned how to find joy in the simplest actions that I used to take for granted. Hey, I can tie my shoes with both hands now! I can reach that thing on the upper shelf! I can eat and drink with my right hand again!

One of the unexpected things that brought me joy was the community I discovered.

Community

One thing that surprised me was just how many other people had had shoulder surgery. As I walked around with a sling on, people would stop me in the most random locations—on the street, in a store, on a train—and say, “Rotator cuff surgery? Ah, yea, I went through that back in…” When the sling came off, and I started doing rehab exercises at the gym or in the sauna, almost every single time, someone would recognize the exercises, and open up about what they went through. Suddenly, I was part of this community of people with busted (but healing) shoulders. We even had a secret handshake:

This exercise is called the wall crawl, where you use your fingers to climb your arm up the wall, as your shoulder muscles aren’t yet strong enough to do it themselves, and just about everyone I met who shared their shoulder surgery stories would do the wall crawl motion as a (not-so) secret “hello.” It was a little weird and creepy at first, but then it became endearing.

Pain, injury, and healing are some of the most universal human experiences. No matter where you grew up, what culture you’re from, or what language you speak, we have all experienced pain, injury, and healing, and these experiences turn out to be a remarkable way to break the ice and bond.

I guess now I’ll be the weirdo who reaches out to other people when I see them in a sling or doing rehab exercises. I’ll be the one doing the slightly creepy hand crawl. To some extent, that’s what this blog post is: a way to share what I went through in case it helps someone else. I hope you’ve found it helpful, and I hope you share your own story in the comments!